Creating Good Jobs Helps Reduce Sickness

People and places do better when there is work around

Having a good job gives us more than cash, it also gives us a sense of purpose and people to chat with. The meaning that comes with work, people to hang out with and, yes, having enough money, makes us healthier. It’s why the decline of good jobs for non-graduates in our post-industrial economy is making people sicker. We can help get sickness down by creating more good jobs for the people and places that don’t currently have them. We can create those good (non-graduate) jobs by building the houses, insulation, and energy infrastructure we need alongside the human capital investments (in healthcare, early years education etc.) we require.

Our starting point in politics should always be: How do we, as a government, help ensure people can live a good life? A good life has several components, among them the ability to: 1) Have a Good Job, 2) Have Enough Cash, and 3) Be Healthy.

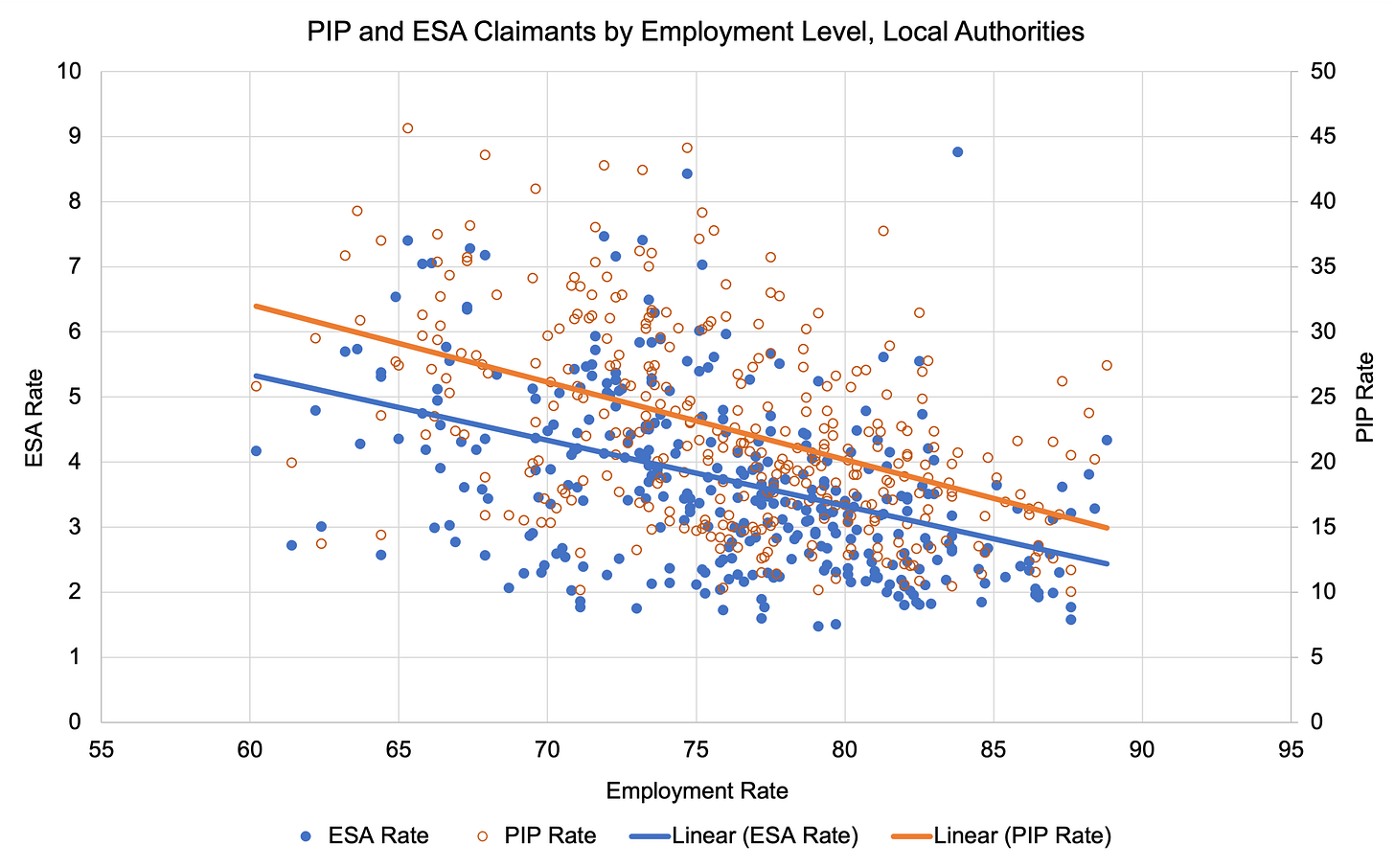

For too many people in this country, it is simply not possible for them to have all three. And it is tied to the fact too many people cannot get a good job. Not because they are not trying, but because there simply are not enough good jobs. A lack of good jobs is why claimant rates for sickness and disability social security payments are higher in areas with lower employment rates (as you can see below).

PIP and ESA Claims are higher in places with lower employment

Source: DWP and ONS

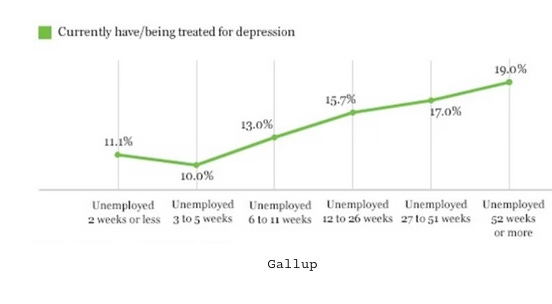

Not having a good job makes people sicker. The lack of purpose, not having enough cash, and less social interaction leads to worse mental health. Worse mental health also leads to worse physical health. Anxiety and depression worsen heart conditions, for example. All in all, not having a good job makes us sicker.

Being unemployed for longer makes people more depressed

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/06/the-mental-health-consequences-of-unemployment/372449/

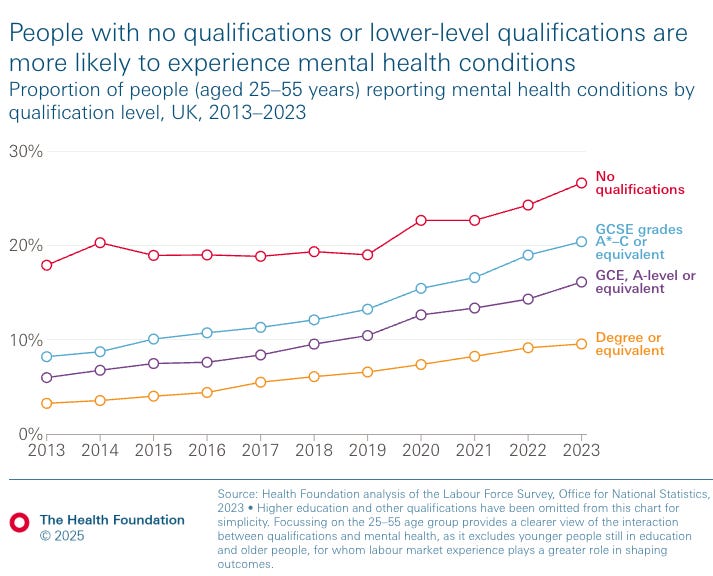

Non-graduates are finding it much harder to find good jobs in the post-industrial economy, and this is making them ill. Where non-graduates could previously leave school and get good jobs in the local factory, they now find it much harder to get any job. Non-graduate men have seen their employment rates plummet by a fifth since the 1980s. When they do find work, it is far more likely to be low-pay and insecure work that does not pay enough to raise a family on. The lack of good jobs is a major reason those with lower qualifications are far more likely to have a mental health conditions and be unable to work because of it.

Fewer qualifications leads to more mental health problems

Source: https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/analysis/mental-health-trends-among-working-age-people

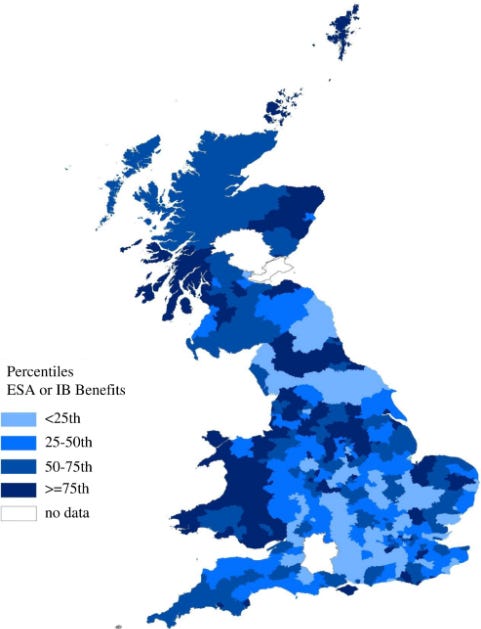

The decline in good non-graduate jobs is a major reason why sickness has risen so dramatically in post-industrial areas of the North, Wales, and the Midlands (as you can see below). Former industrial areas that do not provide good jobs now have the lowest life expectancy and the highest proportion of people on incapacity benefits. The areas that saw the highest levels of unemployment as the country deindustrialised during the 1980s and the 1990s are precisely those that have the fewest good jobs today.

Incapacity benefit claims are higher in post-industrial places

Creating good jobs for the people and places that need them will help make us healthier. The crucial thing in any job creation program is that we take people as they are, not how we wish they would be. We have to intentionally create good jobs and provide the training required for those with fewer qualifications.

The good news is that we need to create a lot of good jobs in the years ahead anyway.

Firstly, we need to build a lot of stuff and all that building needs builders. We need to build 1.5 million homes, insulate many more, and build energy infrastructure. Over 80% of jobs in the construction sector are (skilled) non-graduate roles. Transport infrastructure and home insulation are worse outside of London. Build what we need, and we will create a lot of good non-graduate jobs in the areas that would benefit the most.

Secondly, we need a lot more people in health and childcare so we can look after our our ageing population and ensure new parents can stay in work. By their very nature, these jobs are more likely to be created in more deprived areas where needs are greater. And these jobs can be created in urban centres where there will be less construction.

Creating good jobs (in post-industrial areas) will help get sickness down by raising incomes and providing both purpose and friendships. Creating these jobs will help us live better lives. And that is the whole point of our politics and our values.

Another point of view is that to deal with adversity in life you need the knowledge, skills and relationship network to do so. You personally learn these things at school and from the people around you. You could call this 'happy life' knowledge and skills. For example, a person who knows how to deal with failure and has a network of family and friends to help them to do so will be happier than someone who doesn't. We can all make a difference by passing these skills and knowledge to those around us and encouraging relationship networks. The importance of these skills for all of us often seems to be missed and problems are instead given a financial explanation (not denying the importance of money if you don't have any). People who are able to live good happy lives will together make a better society with better employers who will create better jobs where people feel appreciated and valued. Perhaps the problem is that many of us are loosing those very skills we need in a world that needs relationships but gives us materialism instead.

I remember that in the 1950’s and early 60s, there was almost no male unemployment or underemployment. There was a seemingly endless supply of factory jobs for men, many of them highly repetitive but pretty secure and able to support a family reasonably by the standards of the time. Very few men were so sick or disabled that they couldn’t find steady, full-time employment.

Of course the figures only included paid employment. Unpaid caring, domestic and similar work was usually done by women. Some of the unpaid caring etc work that was done by women now appears in the figures as economic activity because it is paid. Still, a huge amount remains as unpaid or voluntary and therefore counts as economically inactive.

Nowadays there is far less repetitive manual employment available. Even low-paid jobs require team working and interpersonal skills, in some cases (e.g. health and care) at a very high level. Unskilled employment scarcely exists.

For a whole range of reasons, disability, sickness or innate capacity, a substantial number of people are never going to get steady paid employment, regardless of benefit cuts and jobcentre nagging.

The strengthening of employees’ rights by the Government is welcome. However, we also need to broaden our perspective on what is socially useful activity. Unpaid caring can be. Voluntary work can be. This should be respected for the social contribution it makes, not demonised as scrounging. It should be encouraged by the benefits system.

Unfortunately, the government seems to prefer to play to the right-wing media gallery on benefit cuts rather than think more deeply about the way society is developing.